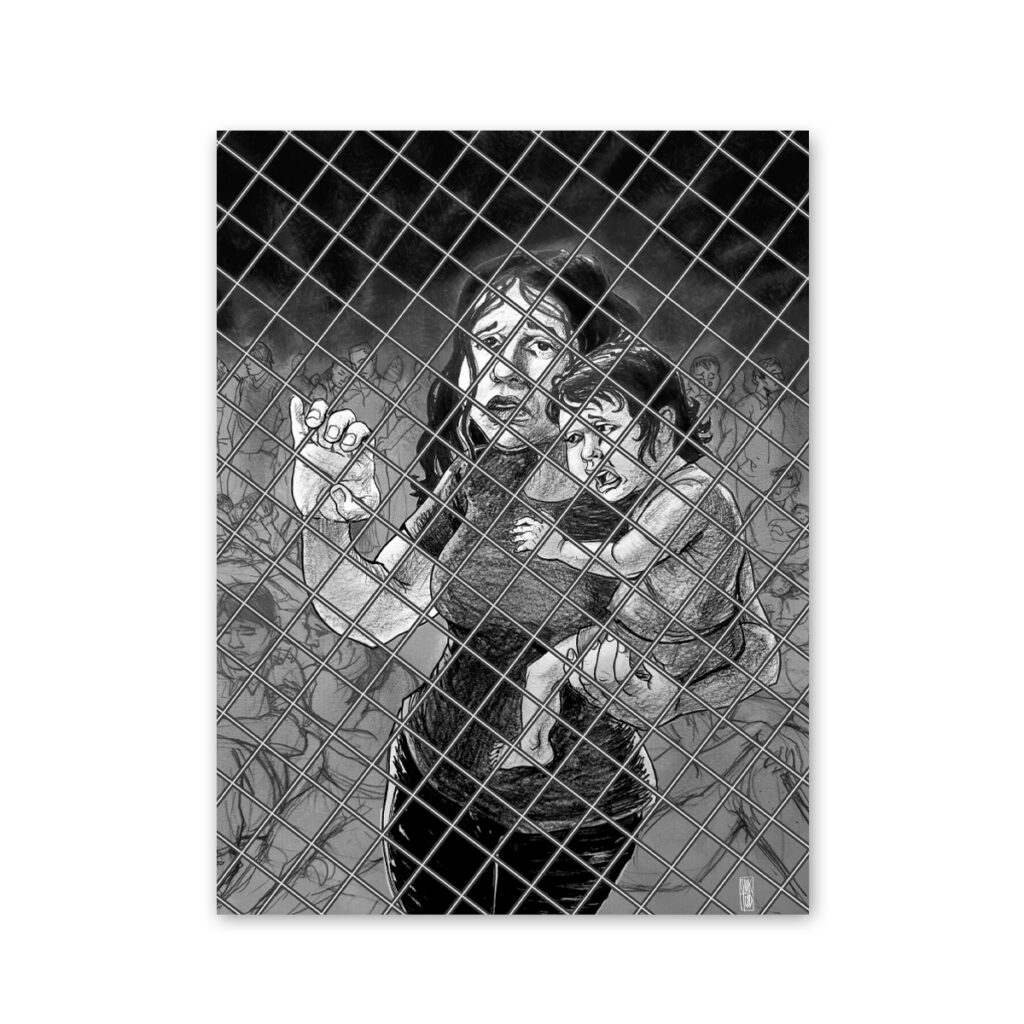

Every day, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) raids rip families apart. As a civil and human rights attorney with two decades of experience assisting immigrants, I have witnessed these dehumanizing practices firsthand: clients detained indefinitely, pressured into economic exploitation or denied due process — all under the guise of “law and order.” These hardworking individuals are torn from their families and communities not for criminal activity, but often for minor paperwork errors or visa lapses or simply for how they look, where they work or how they speak, destroying the lives they’ve built in the process. Although American law treats immigration issues as civil matters, those detained in U.S. immigration facilities often face conditions far worse than those in American prisons.

Every day, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) raids rip families apart. As a civil and human rights attorney with two decades of experience assisting immigrants, I have witnessed these dehumanizing practices firsthand: clients detained indefinitely, pressured into economic exploitation or denied due process — all under the guise of “law and order.” These hardworking individuals are torn from their families and communities not for criminal activity, but often for minor paperwork errors or visa lapses or simply for how they look, where they work or how they speak, destroying the lives they’ve built in the process. Although American law treats immigration issues as civil matters, those detained in U.S. immigration facilities often face conditions far worse than those in American prisons.

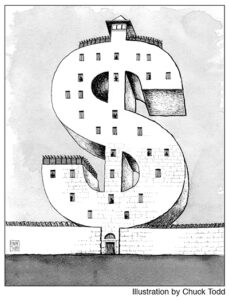

This is no accident. The U.S. economic system has a long history of criminalizing marginalized populations, especially immigrants, people of color and the poor. What makes the current immigration “crisis” particularly evil is the privatization of immigration detention centers.

Today, approximately 90% of ICE detainees are held in privately operated facilities.1 The companies that own these centers knowingly and happily earn profits derived from a system that relies on the control, exploitation and racialized oppression inherent in today’s immigration policy.

While the fact that the modern-day robber barons of the privatized immigration detention industry are making money off of racism and human suffering is horrendous, it is not new. For centuries, American corporations have exploited the most vulnerable in our society.

This article discusses that history and explains how today’s immigration system continues the historical patterns that encourage structural racism and exploitation. By situating modern immigration detention within this broader historical framework, we can understand that it is not an aberration, but part of a long-standing continuum of racialized and class-based exploitation in the United States.

I. America’s History of Racialized Labor Exploitation: Debt Peonage, Chinese Railroad Laborers and Braceros

The history of labor exploitation in the United States is deeply intertwined with race, immigration and capitalism. The most obvious example of this is slavery.

Well before Great Britain had North American colonies, businesses were profiting from enslaved labor. The world’s oldest multinational corporation — the Dutch East India Company — made its money by shipping humans from Africa to the “New World.”2 Lloyd’s of London, one of today’s largest global companies, began by insuring slave ships.3 These and other examples show the early international incentive to exploit people who had no choice in the matter.

By the time the U.S. became an independent nation, slavery was a tentpole of its economy. At one point, the Mississippi Valley region had more millionaires per capita than anywhere else in the nation.4 By some estimates, the accumulated wealth in enslaved people exceeded eight billion dollars.5 And the profits didn’t stop at the Mason- Dixon line. Northern factories refined agricultural products picked by enslaved hands. Companies like New York Life and JP Morgan profited by financing and insuring slave labor.6

While slavery ended, the exploitation of vulnerable communities of color did not. Three examples of this phenomenon are debt peonage, the exploitation of Chinese railroad workers and the Bracero program.

Debt Peonage

After slavery ended, the Freedpeople needed work. Southern farmers still needed harvesting and other forms of labor. The sharecropping system addressed these needs.

Sharecroppers agreed to tend to a plot of land owned by plantation owners, landowners and merchants who owned large plots of farmland. The sharecroppers paid the “rent” on the parcel, as well as any costs associated with seeds or equipment, by giving the owner a portion of their crops at the end of the season.7 While this might sound like a fair arrangement, many landowners took advantage by fraudulently adding false charges to their farmers’ debts, purposefully underestimating the value of the crops, inflating the costs of farming equipment, offering usurious loans, charging high fees at company stores on the land and other immoral practices.8 The sharecroppers, who depended on successful farming seasons to earn money, were usually only one bad crop away from substantial debt.

Sharecroppers agreed to tend to a plot of land owned by plantation owners, landowners and merchants who owned large plots of farmland. The sharecroppers paid the “rent” on the parcel, as well as any costs associated with seeds or equipment, by giving the owner a portion of their crops at the end of the season.7 While this might sound like a fair arrangement, many landowners took advantage by fraudulently adding false charges to their farmers’ debts, purposefully underestimating the value of the crops, inflating the costs of farming equipment, offering usurious loans, charging high fees at company stores on the land and other immoral practices.8 The sharecroppers, who depended on successful farming seasons to earn money, were usually only one bad crop away from substantial debt.

As the debts ballooned, sharecroppers often found themselves unable to repay the money that they “owed.” Here’s where the debt peonage system came in. Some sharecropping contracts stated that tenant farmers could not leave the property until their debts were fully paid. They also earned no money for themselves until the money was repaid. As such, sharecropping debts could force people into free work for years.9

Though both African Americans and whites worked in the sharecropping system,10 the Freedpeople were particularly vulnerable to the system. When slavery ended, the Freedpeople had no land and no money. These deficiencies placed them at a definite disadvantage in the South’s agrarian economy. Without land to farm (or the money to buy equipment or pay workers to properly farm it), sharecropping was often the only economic option.

Worse, the media assisted in the exploitation of Black laborers by supplying negative narratives that justified systems like sharecropping and debt peonage. For instance, Harvard professor Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr., has noted that during the Reconstruction Era, outlets such as The Atlantic Magazine reported that African Americans were “lazy, strangely shaped, and distinct from white people.”11 Popular books carried the false narrative that African Americans had actually been happy under slavery and were dismayed by its end.12 These lies made it difficult to challenge the harm that these systems caused.

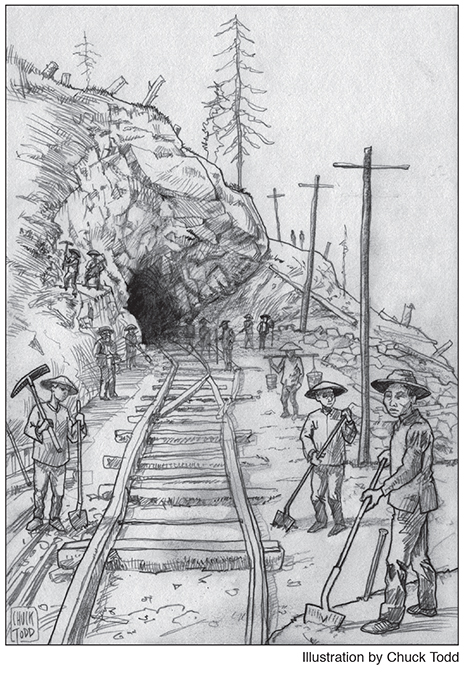

Chinese Laborers

In the late 1800s, the U.S. government funded private companies to build the Transcontinental Railroad to connect the eastern and western coasts of the U.S. Few whites volunteered for the difficult and dangerous work,13 so Chinese migrants took on the task.

The railroad’s path wound through high mountain peaks. In the summer, the brutal heat caused dehydration and other conditions.14 Winters brought snow and avalanches.15 Building the railroad involved blasting tunnels through mountains, laying tracks over treacherous terrain and other dangerous tasks.16 Chinese workers were placed in rickety baskets and lowered down treacherous mountain slopes to place explosives 17— explosives that they had to successfully light before being moved out of harm’s way. While accurate data wasn’t kept at the time, and the numbers are unclear, current reports estimate that as many as 1,200 Chinese workers died during the railroad construction projects.18

Despite the hazards, Chinese rail laborers often earned one-third of what whites received for the same work.19 Worse, while many rail companies provided necessities like food and lodging for their white employees, they charged Chinese laborers for the same items, making it difficult for workers to become financially independent.20

As they had with Freedpeople in the post-bellum South, newspapers, politicians and community leaders in the West depicted Chinese migrants as morally corrupt and unassimilable.21 While some portrayed the migrants as hard-working, even this backfired. Their solid work ethic allowed other whites to argue that they would take jobs from white Americans.22 Politicians used the anti-Chinese sentiment to pass laws aimed at segregating the workers and destroying their cultural traditions.23 The hatred culminated in Congress passing the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. The law became the first in the nation to limit the immigration of a particular race or nationality.24 Coupled with the anti-miscegenation laws in many states, it deprived Chinese workers of the ability to marry and have a family in the U.S. as no Chinese women could be brought in after the Chinese Exclusion Act passed. The law was not repealed until December 1943.

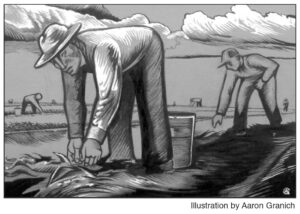

Braceros

In the aftermath of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, thousands of Americans joined the military. But as the war went on, the need for soldiers created a labor shortage in the U.S.

In 1942, the United States and Mexico created a plan to address the U.S. labor shortage. Mexico agreed to let millions of its male citizens go to the U.S. on special short-term work visas.25 These workers, termed “Braceros” (Spanish for “Laborers”), often worked in agriculture, though some also worked in mining and on railroads.

Upon their arrival, each Bracero signed a contract with an American employer.26 Although the contracts required certain wage and workplace protections, the Braceros were forced to work long hours in extreme weather conditions with no regulations on breaks or rest periods.27 Additionally, they were forced to use outdated and dangerous tools, exposed to harsh chemicals and often lacked basic sanitation and medical facilities.28 Worse, contractors often withheld wages to prevent workers from leaving, effectively creating a system similar to debt peonage.

Despite these issues, Braceros were depicted in most government propaganda and media as industrious workers.29 However, this reinforced the stereotype that Latino laborers are obedient and expendable. It also led to widespread, though largely false, allegations that Braceros were driving down wages for American workers.30 Sadly, this branding stuck. During the Bracero Program, the U.S. implemented the racist “Operation Wetback” — a mass deportation campaign against undocumented Mexican workers.31 Thousands of Mexican Americans and naturalized U.S. citizens from Mexico were deported during this time. 32

Summary

Throughout U.S. history, private corporations have targeted vulnerable populations and systematically exploited them in pursuit of profits. The pattern is consistent: populations with little economic or political power are targeted by corporations to do dangerous work. Corporations profit. Once their abuses are exposed, major campaigns — frequently led or supported by the government or media — are created to demonize the exploited population to further weaken their political and social capital and to allow non-affected populations to turn a blind eye to the injustices.

II. Public Pain, Private Profit

Like the sharecroppers, Chinese rail workers and Braceros, the incarcerated are socially and economically vulnerable for many reasons. People in America’s jails and prisons are far more likely than those who are not to have serious physical and mental health issues.33 Most were raised in poverty.34 Nearly two-thirds have not completed high school.35 Despite the fact that they clearly need help and support, a majority of Americans still support “tough-on-crime” policies.36 The stubbornness of these attitudes is likely attributable to the constant (and usually racialized) fearmongering of the media and certain politicians about crime.

America’s inmates are also vulnerable because the conditions of their confinement are completely beyond their control. It is distasteful to take advantage of such vulnerable people. Yet, private companies have been doing exactly that since the 1800s.

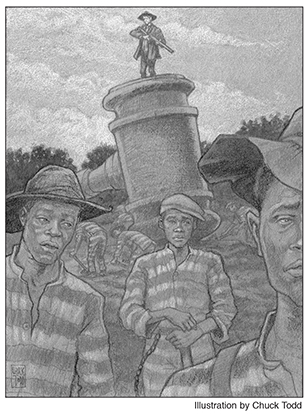

After the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery, plantation owners could no longer rely on forced unpaid labor. However, the text of the Thirteenth Amendment reads, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States….”37 Southern states quickly realized that they could use the amendment’s criminal conviction loophole to replace slave labor with labor from incarcerated people. They rushed to criminalize “offenses” such as loitering, failing to carry proof of employment, stealing food and even walking on grass.38 The states could then force the “duly convicted” prisoners to work for free.

After the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery, plantation owners could no longer rely on forced unpaid labor. However, the text of the Thirteenth Amendment reads, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States….”37 Southern states quickly realized that they could use the amendment’s criminal conviction loophole to replace slave labor with labor from incarcerated people. They rushed to criminalize “offenses” such as loitering, failing to carry proof of employment, stealing food and even walking on grass.38 The states could then force the “duly convicted” prisoners to work for free.

States profiting from free labor was bad enough, but Southern states created a new revenue stream called convict leasing. In convict leasing, a state would release a certain number of prisoners to a company.39 The companies got free labor while the state collected a substantial fee.40 Of course, the convicted persons themselves — nearly all of whom were poor and African American — never saw a dime.41

Economic exploitation was only one part of the plan. Convict leasing subjected workers to brutal work conditions including “beatings, the proliferation of various diseases, starvation, inadequate clothing and vermin infestation.”42 Eventually, exposés about the brutality of the system and protests from the labor movement brought convict lease agreements into disfavor.43

Undeterred, states and corporations found other ways to obtain free labor. Richard Nixon’s 1968 presidential campaign focused on “law and order.”44 In 1971, he began the infamous War on Drugs.45 Fueled by policies that targeted African Americans and Latinos, the War on Drugs exploded the U.S. prison population.46 In 1970, the U.S. incarceration rate was 96 per every 100,000 persons.47 By 1980, the number had jumped to 133 per 100,000.48 In the 1990s, even Democratic politicians like President Bill Clinton adopted allegedly “tough-on-crime” policies.49 Between 2006 and 2008, the U.S. incarceration rate reached a record high of 1,000 inmates per 100,000 adults.50

Private prison companies took advantage of this population surge. The Corrections Corporation of America (now CoreCivic), GEO Group and other companies profited by entering into contracts to operate prisons. While the billion-dollar industry flourished, the people inside suffered. According to one report, assaults on prisoners were far more common in private than in public prisons.51

III. Immigration: Incarceration’s New Frontier

By 2010, U.S. incarceration numbers began to plateau.52 Private prison corporations found a new opportunity: immigration detention.

For years, immigration detentions were rare.53 However, in the 1990s, laws like the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) and the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA) increased the government’s authority to detain immigrants for even minor offenses such as visa overstays, paperwork errors or even minor traffic violations.54 This criminalization of the immigration process — colloquially known as “crimmigration”55 — created a new population of people to be jailed. Private corporations quickly seized on the new market.

For years, immigration detentions were rare.53 However, in the 1990s, laws like the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) and the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA) increased the government’s authority to detain immigrants for even minor offenses such as visa overstays, paperwork errors or even minor traffic violations.54 This criminalization of the immigration process — colloquially known as “crimmigration”55 — created a new population of people to be jailed. Private corporations quickly seized on the new market.

Today, approximately 90% of ICE detainees are held in privately operated facilities.56 This large market share gives private detention companies an incentive to support harsher immigration laws and crueler enforcement.

It should come as no surprise that private detention companies support Donald Trump and similar politicians. Their extreme views on immigration translate into extreme immigration policies. Extreme policies increase the need for detention facilities which makes immigration detention properties more profitable. Indeed, stock prices for both CoreCivic and GEO Group skyrocketed in the immediate aftermath of Trump’s second election.57 In a February 2025 earnings call, CoreCivic CEO Damon Hininger said that Trump’s second election had ushered in “significant growth opportunities, perhaps the most significant growth in our company’s history over the next several years.”58

Linking Today’s Immigration Regime to the Earlier Systems of Exploitation

The parallels between historical capitalist schemes like debt peonage and contemporary private immigration detention are stark and deeply troubling. Again, those systems exploited the labor of vulnerable populations and forced them to work in awful conditions. These companies — and sometimes the government and the media — then demonized those groups to forestall any critique and further limit the marginalized group’s political and social capital. The same is true here.

A Vulnerable Population

Like the sharecroppers, Chinese laborers and Braceros of the past, undocumented migrants are a vulnerable population. In 2022, 50% of undocumented migrants had not completed high school.59 Roughly two-thirds struggle with English proficiency.60 These factors, combined with employers and landlords holding the threat of reporting the undocumented worker to ICE, likely explain why undocumented immigrants earn about one-third less than those with legal immigration status.61 The isolation and stigma of immigration detention add another layer of vulnerability.

Exploitation

In past eras, business magnates became rich while sharecroppers, Chinese laborers and Braceros made little money in poor conditions. The same is true today.

In past eras, business magnates became rich while sharecroppers, Chinese laborers and Braceros made little money in poor conditions. The same is true today.

In the first quarter of 2025, CoreCivic reported a total revenue of $488.6 million.62 During the same period, GEO Group’s total revenue was $604.6 million.63 At the same time, both companies have faced lawsuits and backlash for paying the detainees at their facilities just $1 per day for their work,64 despite the fact that the undocumented status is civil, not criminal, and hence not subject to the Thirteenth Amendment’s exclusion of convicted individuals from those protected against slavery.

Conditions

As private companies rush to increase their profits, detainees suffer. Consider these examples:

• In a recent lawsuit, a former CoreCivic employee alleged that the company hired just two nurses to care for 1,500 detainees.65

• The federal government’s own report uncovered a multitude of failures to provide care for even simple injuries, including cuts and other wounds.66

• In June 2025, detainees at GEO Group’s Newark, NJ, facility protested the food service issues at the center.67 The “meal” that sparked the protest consisted of two pieces of bread — nothing more.

• A 2016 oversight report from the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) found that 17 privately owned ICE facilities had inedible food.68

• In a story on private facilities, The New York Times reported: “Some immigrants have gone a week or more without showers. Others sleep pressed tightly together on bare floors.”69

• A DHS oversight report said that GEO Group’s facility in Adelanto, CA had “detainee bathrooms that were in poor condition, including mold and peeling paint on walls, floors and showers, and unusable toilets.”70

• In August 2024, GEO Group allegedly retaliated against striking detainees by cutting off the air conditioning at the facility during a triple-digit heatwave. 71

Demonization

Demonization

Just as many politicians and media outlets portrayed sharecroppers and Braceros as bad people, today’s politicians have made many derogatory comments about undocumented migrants. Chief among them is Donald Trump. He began his 2016 campaign by stating, “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best … bringing drugs, bringing crime, they’re rapists.”72 He has compared unauthorized immigrants to “snakes that bite.”73 During his September 2024 debate against Vice President Kamala Harris, Trump alleged that Haitian immigrants in Ohio were “… eating the dogs … they’re eating the cats.”74 Earlier this year, he said that undocumented farmworkers are “naturally suited” for field labor.75 Comments like these — especially from a person in a powerful position — encourage the general public to view migrants negatively. Worse, they make it easier for companies like CoreCivic and GEO Group to justify their abuses.

IV. Conclusion — Toward Justice, Not Cages

Understanding the historical continuity between the exploitative systems of yesteryear is crucial. Contemporary detention practices are not anomalies; they are extensions of centuries-long strategies in which corporations and governments extract labor, enforce structural compliance and exploit vulnerability for profit. By recognizing these patterns, advocates can better argue for systemic alternatives that prioritize human dignity, family unity and equitable access to justice over corporate revenue and punitive control.

The widespread normalization of confinement as a response to migration fosters public acceptance of punitive state practices. The solution is not reform; it is the total abolition of the current immigration system, starting with ICE.

Abolition may seem a drastic step. However, borders are nothing more than imaginary lines created to serve elites. They shift over time. In fact, many of the states in the Southwestern U.S. were once part of Mexico. Because borders are imaginary, we are free to reimagine what they mean.

However, abolition will take time. In the interim, we can work toward:

• Abolishing ICE.

• Ending all private immigration detention contracts with companies like CoreCivic and GEO Group.

• Passing legislation that ends the economic exploitation of immigration detainees.

• Demanding true oversight and accountability at immigration detention facilities.

• Repealing mandatory detention policies and criminal gateways for civil immigration infractions.

• Investing in community-based alternatives that center care, legal representation and humane support.

• Uniting immigrant rights, labor justice, racial equity, and prison abolition movements to address the interconnected struggles.

• Boycotting — or otherwise not supporting — investors and companies that fund or do business with private prison corporations such as CoreCivic and GEO Group.

Incarceration does not create safety. Rather, safety comes from strong communities. When we treat migrants well, we make it safe for them to interact with schools, police, hospitals, churches and other crucial pillars. It is these connections — not policing, not detention, and certainly not privatized detention — that make our communities stronger. By redirecting resources from profit-driven detention toward human-centered policies, the United States can move toward a society where immigration is treated with dignity, fairness and humanity.

________________________________

1. Meg Anderson,“Private Prisons and Local Jails Are Ramping up as ICE Detention Exceeds Capacity.” NPR, June 4, 2025. https://www. npr.org/2025/06/04/nx-s1-5417980/private-prisons-and-local-jails-are-ramping-up-as-ice-detention-exceeds-capacity.

2. “‘The World’s Oldest Trade:’ Dutch Slavery and Slave Trade in the Indian Ocean in the Seventeenth Century,” History Cooperative, June 19, 2020. https://historycooperative.org/journal/worlds-oldest-trade-dutch-slavery-slave-trade-indian-ocean-seventeenth-century/.

3. “The Transatlantic Slave Trade.” Accessed August 23, 2025. https:// www.lloyds.com/about-lloyds/history/the-trans-atlantic-slave-trade.

4. Greg Timmons, “How Slavery Became the Economic Engine of the South,” HISTORY, March 6, 2018. https://www.history.com/articles/ slavery-profitable-southern-economy.

5. Ta-Nehisi Coates, “What Cotton Hath Wrought,” The Atlantic, July 30, 2010. https://www.theatlantic.com/personal/archive/2010/07/ what-cotton-hath-wrought/60666/.

6. Rachel Swarns, “Insurance Policies on Slaves: New York Life’s Complicated Past,” The New York Times, December 18, 2016. https:// www.nytimes.com/2016/12/18/us/insurance-policies-on-slaves-new-york-lifes-complicated-past.html.

7. “Slavery By Another Name,” “Sharecropping,” PBS, February 12, 2012. Accessed August 23, 2025. https://www.pbs.org/tpt/ slavery-by-another-name/themes/sharecropping/.

8. “Peonage and the Supreme Court,” EBSCO Research Starters. Accessed August 23, 2025. https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/ law/peonage-and-supreme-court.

9. Ibid.

10. “Sharecropping,” Digital History. Accessed August 23, 2025. https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=2& psid=3100#:~:text=During%20Reconstruction%2C%20former%20 slaves%2D%2D,to%20work%20for%20large%20landowners.

11. Rann Miller, “How Racist Ideas Shaped the Era of Reconstruction,” AAIHS, August 18, 2020. https://www.aaihs.org/how-racist-ideas-shaped-the-era-of-reconstruction/.

12. Ibid.

13. Lesley Kennedy, “Building the Transcontinental Railroad,” HISTORY, May 10, 2019. https://www.history.com/articles/transcontinental-railroad-chinese-immigrants. See also “Key Questions – Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project.” Accessed August 23, 2025. https://web.stanford.edu/group/chineserailroad/ cgi-bin/website/faqs/.

14. Lakshmi Gandhi, “The Transcontinental Railroad’s Dark Costs,” HISTORY, October 8, 2021. https://www.history.com/articles/ transcontinental-railroad-workers-impact.

15. Ibid.

16. Supra at note 13.

17. “Geography of Chinese Workers Building the Transcontinental Railroad.” Accessed August 23, 2025. https://web.stanford.edu/group/ chineserailroad/cgi-bin/website/virtual/.

18. “Chinese Immigrants and the Building of the Transcontinental Railroad,” Digital History. Accessed August 23, 2025. https://www. digitalhistory.uh.edu/voices/china1.cfm.

19. “Chinese Labor and the Iron Road,” Golden Spike National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service).” Accessed August 23, 2025. https://www.nps.gov/gosp/learn/historyculture/chinese-labor-and-the-iron-road.htm.

20. “Chinese Historical & Cultural Project — Chinese Railroad Workers.” Accessed August 23, 2025. https://chcp.org/Chinese- Railroad-Workers.

21. Digital Public Library of America. “A Nation Transformed.” Accessed August 23, 2025. https://dp.la/exhibitions/ transcontinental-railroad/nation-transformed/connection-exclusion.

22. Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest. Accessed August 23, 2025. https://www.washington.edu/uwired/outreach/cspn/Website/ Classroom%20Materials/Pacific%20Northwest%20History/Lessons/ Lesson%2015/15.html.

23. Ibid.

24. “Chinese Exclusion Act (1882),” National Archives, September 8, 2021. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/chinese-exclusion-act.

25. Dani Thurber, “Research Guides: A Latinx Resource Guide: Civil Rights Cases and Events in the United States: 1942: Bracero Program.” Library of Congress Research guide. Accessed August 23, 2025. https://guides.loc.gov/latinx-civil-rights/bracero-program.

26. Jessie Kratz, “The Bracero Program: Prelude to Cesar Chavez and the Farm Worker Movement,” Pieces of History, September 27, 2023. https://prologue.blogs.archives.gov/2023/09/27/the-bracero-program-prelude-to-cesar-chavez-and-the-farm-worker-movement/.

27. “Labor Practices · California’s Bracero Program · Santa Clara University Digital Exhibits.” Accessed August 23, 2025. https://dh.scu. edu/exhibits/exhibits/show/california-s-bracero-program/human-rights-concerns/.

28. Jessie Kratz, “The Bracero Program: Prelude to Cesar Chavez and the Farm Worker Movement.” Pieces of History, November 19, 2024. https://prologue.blogs.archives.gov/2023/09/27/the-bracero-program-prelude-to-cesar-chavez-and-the-farm-worker-movement/.

29. J. R. García, “Bracero Program, 1942–1964,” in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History (Oxford University Press, 2018). Accessed August 23, 2025. https:// oxfordre.com/latinamericanhistory/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.001.0001/acrefore-9780199366439-e-590.

30. “Mexican Bracero Exclusion Failed to Raise Wages or Employment for Domestic Farm Workers in the U.S.,” Dartmouth, February 10, 2017. https://home.dartmouth.edu/news/2017/02/mexican-bracero-exclusion-failed-raise-wages-or-employment-domestic-farm-workers-us.

31. EJI, “July 15, 1954, U.S. Government Stages Mass Deportations in The American Southwest,” n.d. https://calendar.eji.org/racial-injustice/jul/15.

32. Ibid.

33. “People in Prison Have Higher Rates of Mental Illness, Infectious Diseases and Poor Physical Health – New Study,’ University of Oxford, Department of Psychiatry, 28 March 2024, Accessed August 23, 2025. https://www.psych.ox.ac.uk/news/people-in-prison-have-higher-rates-of-mental-illness-infectious-diseases-and-poor-physical-health-2013-new-study.

34. Leah Wang, Wendy Sawyer, Tiana Herring and Emily Widra,“Beyond the Count: A Deep Dive into State Prison Populations,” Prison Policy Initiative, April 2022, Accessed August 23, 2025. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/beyondthecount.html.

35. Ibid.

36. Megan Brenan, “Americans More Critical of U.S. Criminal Justice System.” Gallup.Com, November 16, 2023. https://news.gallup.com/ poll/544439/americans-critical-criminal-justice-system.aspx.

37. National Archives. “13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Abolition of Slavery (1865),” May 10, 2022. https://www.archives.gov/ milestone-documents/13th-amendment/.

38. Ellen Terrell, “The Convict Leasing System: Slavery in Its Worst Aspects,” The Library of Congress, June 17, 2021. https://blogs.loc. gov/inside_adams/2021/06/convict-leasing-system.

39. “Peonage and the Supreme Court,” EBSCO Research Starters.” Accessed August 23, 2025. https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/ law/peonage-and-supreme-court.

40. Ibid.

41. Kiana Knight,“Convict Leasing in the Family,” AAIHS, January 17, 2024. https://www.aaihs.org/convict-leasing-in-the-family/.

42. Courtney Howell, “Convict Leasing: Justifications, Critiques, and the Case for Reparations,” Virginia Tech Undergraduate Historical Review 5, no. 1 (2017). https://doi.org/10.21061/vtuhr.v5i1.

43. Supra at note 38.

44. Leonidas K. Cheliotis, “Manufacturing Concern: Inside Richard Nixon’s ‘Law and Order’ Campaign.” Criminology & Criminal Justice, August 21, 2024, 17488958241266730. https://doi org/10.1177/ 17488958241266730.

45. Nazish Dholakia,“Fifty Years Ago Today, President Nixon Declared the War on Drugs,” Vera Institute of Justice, July 7, 2018. https://www.vera.org/news/fifty-years-ago-today-president-nixon-declared-the-war-on-drugs.

46. “Mass Incarceration Trends,” The Sentencing Project, May 21, 2024. https://www.sentencingproject.org/reports/ mass-incarceration-trends/. See also Nkechi Taifa, “Race, Mass Incarceration, and the Disastrous War on Drugs,” Brennan Center for Justice, May 17, 2021. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/ analysis-opinion/race-mass-incarceration-and-disastrous-war-drugs.

47. Margaret Wener Cahalan and Lee Anne Parsons, “Historical Corrections Statistics in the United States, 1850- 1984,” U. S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Report of Work Performed by Westat, Inc., December 1986. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/ pub/pdf/hcsus5084.pdf.

48. Ibid.

49. Carrie Johnson, “20 Years Later, Parts Of Major Crime Bill Viewed As Terrible Mistake.” Law. NPR, September 12, 2014. https://www.npr. org/2014/09/12/347736999/20-years-later-major-crime-bill-viewed-as-terrible-mistake.

50. John Gramlich, “America’s Incarceration Rate Falls to Lowest Level since 1995,” Pew Research Center, August 16, 2021. https:// www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2021/08/16/americas-incarceration-rate-lowest-since-1995/.

51. James Austin, Ph.D., and Garry Coventry, Ph.D., Emerging Issues on Privatized Prisons, BJA Monograph (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Assistance, February 2001), NCJ 181249, prepared by the National Council on Crime and Delinquency, PDF file. Office of Justice Programs. https://www.ojp. gov/pdffiles1/bja/181249.pdf.

52. James Austin, Garry Coventry and National Council on Crime and Delinquency. Emerging Issues on Privatized Prisons. Monograph. Bureau of Justice Assistance. Bureau of Justice Assistance, 2001. https:// www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/bja/181249.pdf.

53. Smita Ghosh and Mary Hoopes, “Learning to Detain Asylum Seekers and the Growth of Mass Immigration Detention in the United States,” Law & Social Inquiry 46, no. 4 (2021), pp. 993–1021. https://doi. org/10.1017/lsi.2021.11.

54. Bobby Hunter and Victoria Yee, “Dismantle, Don’t Expand: The 1996 Immigration Laws,” NYU School of Law, Immigrant Rights Clinic, 2017. https://www. law.nyu.edu/sites/default/files/upload_documents/1996Laws_FINAL_Report_4.28.17.pdf.

55. “Understanding Crimmigration,” Advocate Magazine, Lewis & Clark Law School, Fall 2024. Accessed August 23, 2025. https://law.lclark.edu/live/ news/54953-understanding-crimmigration.

56. Meg Anderson,“Private Prisons and Local Jails Are Ramping up as ICE Detention Exceeds Capacity,” Immigration. NPR, June 4, 2025. https://www.npr.org/2025/06/04/nx-s1-5417980/private-prisons-and-local-jails-are-ramping-up-as-ice-detention-exceeds-capacity.

57. Christiaan Hetzner, “Trump’s Election Win Sends Private Prisons Stocks Soaring as Investors Anticipate Hard Crackdown on Migration,” Fortune, November 7, 2024. Accessed August 23, 2025. https://fortune.com/2024/11/07/president-donald-trump-election-immigration-border-detention-ice-geo-group-corecivic/.

58. Laura Romero, “Executives at private prison firm CoreCivic expect ‘significant growth’ due to Trump’s policies.” ABC News, February 12, 2025. Accessed August 23, 2025. https://abcnews. go.com/US/executives-private-prison-firm-corecivic-expect-significant-growth/story?id=118758271.

59. Evin Millet and Jacquelyn Pavilon, “Demographic Profile of Undocumented Hispanic Immigrants in the United States,” Center for Migration Studies of New York, October 2022. https://www.cmsny.org/ wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Hispanic_undocumented.pdf.

60. Jeffrey S. Passel and D’Vera Cohn, “U.S. unauthorized immigrants are more proficient in English, more educated than a decade ago,” Pew Research Center, May 23, 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2019/05/23/u-s-undocumented-immigrants-are-more-proficient-in-english-more-educated-than-a-decade-ago/.

61. George J. Borjas and Hugh Cassidy, “The Wage Penalty to Undocumented Immigration,” Labour Economics 61 (December 2019): 101757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2019.101757.

62. CoreCivic Reports First Quarter 2025 Financial Results, press release, CoreCivic, Inc., May 7, 2025, accessed August 23, 2025, on CoreCivic Investor Relations website. ir.corecivic.com.

63. The GEO Group Reports First Quarter 2025 Results, press release, The GEO Group, Inc., May 7, 2025, accessed August 23, 2025, investors.geogroup.com.investors.geogroup.com.

64. McKenzie Funk,“An ICE Contractor Is Worth Billions. It’s Still Fighting to Pay Detainees as Little as $1 a Day to Work,” ProPublica, March 19, 2025. https://www.propublica.org/article/geo-group-ice-detainees-wage.

65. Gustavo Solis, “Lawsuit against ICE detention center highlights medical neglect complaints,” KPBS News, April 16, 2024. https://www.kpbs.org/ news/border-immigration/2024/04/16/ lawsuit-against-ice-detention-center-highlights-medical-neglect-complaints.

66. Tom Dreisbach, “Government’s own experts found ‘barbaric’ and ‘negligent’ conditions in ICE detention.” Investigations. NPR, August 16, 2023. https://www.npr. org/2023/08/16/1190767610/ice-detention-immigration-government-inspectors-barbaric-negligent-conditions.

67. Four Men Escape from Migrant Facility, New York Times, June 14, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/06/12/ nyregion/newark-migrant-detention-center-disturbance.html, accessed August 23, 2025.

68. Ibid.

69. “Concerns Grow Over Dire Conditions in Immigrant Detention,” New York Times, June 28, 2025, https://www. nytimes.com/2025/06/28/us/immigrant-detention-conditions.html?searchResultPosition=1, accessed August 23, 2025.

70. Concerns about ICE Detainee Treatment and Care at Four Detention Facilities, OIG-19-47 (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Inspector General, June 3, 2019), https://www.oig.dhs. gov/sites/default/files/assets/2019-06/OIG-19-47-Jun19.pdf.

71. Victoria Valenzuela, “More than 60 ICE detainees on hunger strike over ‘inhumane’ living conditions,” The Guardian, August 26, 2024. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/article/2024/aug/26/ immigration-customs-enforcement-ice-hunger-strike-california.

72. Eric Deggans, “NBC Dumps Donald Trump Over Comments on Mexican Immigrants,” NPR, June 29, 2015. https://www.npr. org/2015/06/29/418641198/nbc-dumps-donald-trump-over-comments-on-mexican-immigrants.

73. Anna Flagg, Andrew Rodriguez Calderón and Geoff Hing, “Trump Often Repeats These False, Misleading Immigration Claims. Here Are the Facts.” The Marshall Project, October 24, 2024. https://www. themarshallproject.org/2024/10/24/fact-check-trump-statements-immigrants-takeaways.

74. Merlyn Thomas and Mike Wendling, “Donald Trump repeats baseless claim about Haitian immigrants eating pets,” BBC, September 15, 2024. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c77l28myezko.

75. Gerren Keith Gaynor, “Trump’s claim that undocumented workers are ‘naturally’ fit for farm labor harkens to racist theory about enslaved blacks,” TheGrio, August 5, 2025. https://thegrio. com/2025/08/05/trumps-undocumented-workers-are-naturally-farm-labor-slavery/.

This article was originally published by Verdict Magazine.