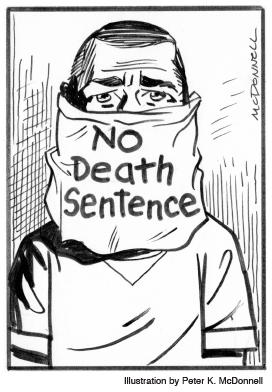

In California, a person cannot be sentenced to death unless 12 jurors first unanimously decide that the person is guilty of the crime, for which death is a possible sentence.1 Then, they must unanimously agree that capital punishment is warranted.2 It is a serious process designed to protect the rights of the accused, uphold the constitutional guarantees of due process, and prevent the state from using its power to kill the innocent.3

In California, a person cannot be sentenced to death unless 12 jurors first unanimously decide that the person is guilty of the crime, for which death is a possible sentence.1 Then, they must unanimously agree that capital punishment is warranted.2 It is a serious process designed to protect the rights of the accused, uphold the constitutional guarantees of due process, and prevent the state from using its power to kill the innocent.3

In July 2020, my client died in a California prison, despite not being sentenced to death as the law requires. Instead, he was, in effect, sentenced to death by a prison system that failed to respond when he contracted COVID-19.

My client’s story is sadly commonplace. When the COVID-19 pandemic reached our shores, thousands of people died while being held in state and federal custody. There was no due process: no judicial ruling or jury deliberation. In fact, some had yet to be adjudicated guilty of any crime. These people died having been too poor to pay for bail and condemned by a carceral system that devalues lives.

My Client’s Story

The first cases of COVID-19 in the U.S. were identified in January 2020.4 Two months later, state and local governments issued “stay-at-home” orders to encourage residents to limit their movement to essential travel.5 On March 24, 2020, Governor Gavin Newsom ordered California prisons to stop accepting inmates for 30 days.6 By April 2020, the risks of COVID-19 were well-known, and many cities and counties had issued mask mandates for indoor spaces.

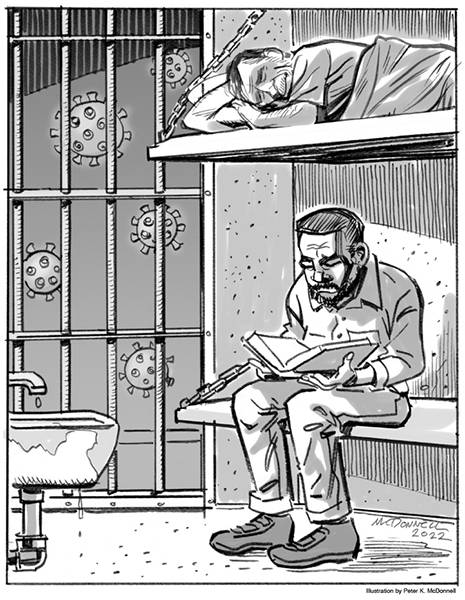

On May 30, 2020, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) approved the transfer of 122 persons from the California Institution for Men in Chino, CA to the San Quentin State Prison. The detention facility in Chino was in the midst of a severe COVID-19 outbreak, with at least 600 people infected, and ten deaths attributed to the virus. Nonetheless, the transferred prisoners were allowed to share open-air cells, bathrooms and mess halls with prisoners confined at San Quentin, which had no active COVID-19 cases at the time. Practically overnight, San Quentin experienced a massive outbreak of COVID-19 infections.

In March 2020, my client was serving a short sentence at San Quentin. His family, particularly his wife, visited him every weekend and called him every week. The family looked forward to his impending release. But it was not to be.

By May 2020, my client, who was 79 years old, had developed a cough that worsened over the following two months. On July 2, he was sent to the hospital after being found unresponsive. There, he was resuscitated and tested positive for COVID-19. The doctors determined that his death was imminent. My client passed away on July 5, 2020. His family had known no details about his medical condition, despite numerous requests to prison and hospital authorities, respectively, in the months and days prior to his death.

Prison officials had known that the situation in prisons was dangerous. On June 13, public health officials sent San Quentin staff an urgent memo warning that the outbreak could morph into “a full-blown local epidemic.” The San Quentin staff ignored the warning. When a local firm offered to supply free COVID-19 testing services for San Quentin prisoners, prison officials twice rejected the offer.

My client’s death was entirely preventable. Prison officials were well aware of the outbreak as well as his advanced age and underlying medical conditions — Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and hypertension. Yet, they did not take the necessary precautions to ensure he (or other senior residents) did not contract COVID-19. My client’s story is just one of the thousands of preventable healthcare tragedies that occur behind bars during the pandemic.

In the following section, I detail how health services in prisons fail our aging, unfit prison population. While the U.S. is home to just four percent of the world’s population, 16 percent of the world’s incarcerated people live here. Just over 2 million Americans are in prison,7 which means that a significant proportion of the U.S. population has been exposed to the failures of the prison health care systems.

Health Care As a Constitutional Right

Health Care As a Constitutional Right

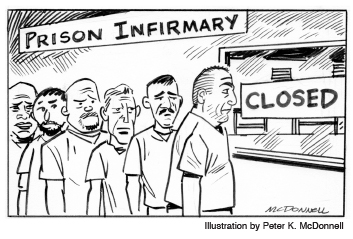

In Estelle v. Gamble,8 the Supreme Court held that prisoners had a constitutional right to basic medical care. Nearly fifty years after the 1976 decision, the prison healthcare apparatus is haphazard at best and irreparably broken at worst, with no national standards for the health care of prisoners.

Experts note that most prison systems suffer from limited technologies and staffing shortages. For example, a 2018 investigation of the James T. Vaughn Correctional Center in Delaware found that many critical positions — especially nursing positions — were vacant, leading to long wait times for patients and burnout for staff.9 The facility’s technology was so outdated that they used Microsoft Word to input patient information, only to cut and paste it into a medical file at a later date. Failures such as these reasonably lead prison patients to lack trust in the prison health system.10

Three likely reasons for the lack of adequate prison health care must be considered. First, prison health systems are grossly underfunded. In 2015, the average state spent roughly $5,700 on each incarcerated patient.11 However, some states spent even less. Louisiana, for instance, allocated just $2,100.12 (For comparison, the average health care expenditure for all Americans in 2020 was just over $12,500.13) Underfunded healthcare services cannot provide incarcerated patients adequate care.

Second, prison health systems often hire and retain staff with troubling work histories. In 2018, for example, Georgia settled two lawsuits regarding staff negligence. One of the doctors accused of negligence had previously lost his New York medical license due to malpractice.14 Not only did Georgia still hire him, but they also allowed him to serve as prison medical director for nine years, during which time patients won $2.5 million in damages in negligence claims.15 Georgia only terminated the doctor after he had killed one patient and left another in a permanent vegetative state. Exposing prisoners to harmful medical staff undoubtedly runs afoul of Estelle v. Gamble.

Third, nearly half of states have privatized some or all of their prison health care operations.16 Private prison health firms have earned a reputation for cutting corners and sacrificing quality. In another Georgia case from 2014, a prison doctor and two nurses recommended that their patient be hospitalized.17 But their manager at Corizon Health, the private provider of prison health services, opposed the transfer.18 The medical team brought in a cardiologist who concurred with their assessment, and then demanded the hospitalization of their patient.19 Corizon, which had a history of depriving needed care,20 relented, but the patient died shortly thereafter. As bad as state-run prison health care can be, the privatized version is far worse. In fact, researchers have consistently found that prison patients fare better in public-run health systems.21

The prison population suffers from more health problems than the general population. Compared to the non-incarcerated population, those housed in prisons are more likely to suffer from chronic conditions such as hypertension, asthma, hepatitis and arthritis.22 Incarcerated persons are also more likely to enter jails and prisons with mental health challenges.23 These illnesses require constant management, accurate medication doses, and adequate follow-up. As the prison population grows older, it will be more challenging for the hobbled prison healthcare system to keep up with their needs.

When COVID-19 Collided with the Prison-Industrial Complex

Prisons in the U.S. are practically tailor-made to spread COVID-19. Prisons did not provide residents with masks immediately,24 leaving prisoners with no option but to fashion their own out of t-shirts or other clothing. Additionally, with broken sinks or spotty plumbing, and no hand sanitizer, which is considered contraband,25 frequent hand washing is not possible.26 With two prisoners sharing a cell that is less than six feet wide, social distancing is an impossibility.27 As these unacceptable conditions made containing COVID-19 a daunting endeavor, prisons failed to safeguard the health and well-being of those in their custody.

U.S. prisons reported 622,968 cases of COVID-19 from March 2020 to September 2022.28 According to the CDC, from March 2020 to February 2021, roughly 2,500 incarcerated persons died from COVID-19 in state and federal prisons. That is, 1.5 out of every 1,000 incarcerated persons died from COVID-19 during this period.29 According to the COVID Prison Project, the rate for those not in prison over the same period was 1.25 deaths per 1,000 people — 20% lower than those incarcerated.

These numbers, as high as they are, may not reflect the full tragedy of the situation in prisons for several reasons. First, while officials initially seemed interested in being transparent about COVID-19 deaths, that interest eventually waned. In the first year of the pandemic, most states made their COVID-19 death and case information publicly available via websites or other methods. But by June 2021, major states like Florida, Georgia and Louisiana abruptly stopped providing researchers and news outlets with data about prison COVID-19 deaths.30

COVID-19 had not stopped spreading in June 2021. In fact, one of the worst COVID-19 waves, the phase initiated by the Delta variant, took hold in July 2021, just after these states stopped sharing data.31

Second, those who contracted COVID-19 while in prison, but who died outside of custody, were not regularly included in data on COVID-19 deaths in prisons.32 The New York Times, for example, reported that the number of COVID-19 deaths in New York prisons could not be accurately counted due to this practice.33 Georgia and Pennsylvania had similar “accounting errors.” Some states, like Missouri, refused to provide the necessary supplemental data.34 These undercounts mean that we may never know the full impact of COVID-19 on imprisoned patients.

Finally, prison patients who contracted COVID-19, but did not die, are at high-risk for post-acute sequelae, commonly known as “long Covid.” Symptoms of long Covid include fatigue, trouble breathing, cardiac symptoms and difficulty thinking or concentrating.35 While little is known about why some people develop long Covid and others do not, we know that the poor and people of color are at greater risk.36 Given that Black and Brown people comprise the majority of the prison population, we can expect that many prisoners are suffering from long Covid or will soon.

Going Forward

Going Forward

Most people do not need to be incarcerated. During the early stages of the pandemic, many states released prisoners. Some did so to reduce overcrowding and limit the spread of the disease. Others targeted populations with special susceptibility to COVID-19 (e.g., the aged or those with pulmonary conditions). These early releases did not compromise public safety as proponents of tough-on-crime policies warned.

A recent Washington Post article chronicled what happened to federal prisoners released due to COVID-19 concerns.37 The researchers followed 11,000 freed individuals. Of those, just 17 committed new offenses after release.38 Just 17 out of 11,000. This low recidivism rate should prompt our society to seriously reconsider our penal system. Everyone may not favor prison abolition as I do. Still, all fair-minded individuals should agree that our current system is fatally broken. It must be replaced with something better, instead of being “repaired” with patchwork fixes that don’t address the structural and social issues that give rise to crime.

I have received numerous phone calls from distraught family members whose loved ones passed away from COVID-19 while incarcerated. Unfortunately, I have to inform them that the law is not on their side. Already, the State of California has asserted various governmental immunities to COVID-related litigation and shields itself under the cover of a medical emergency, claiming the state has done its best under the circumstances — circumstances they created.

My client’s death, like the deaths of so many others in his situation, was unnecessary. But in pursuing his case, I hope not only to bring his family justice, but also to shed light on the larger problems endemic to our criminal justice system. As Nelson Mandela wisely stated, No one truly knows a nation until one has been inside its jails. A nation should not be judged by how it treats its highest citizens, but its lowest ones.

The deliberate indifference to human lives within prisons during the COVID-19 pandemic makes clear that the United States fails to recognize that the poor medical treatment, or lack thereof, in prisons amounts to cruel and unusual punishment under the 8th Amendment. That is why we must act and hold state and federal governments accountable for how they treat and care for those of us who pass through the prison systems in the United States.

________________________________

- Cal. Penal Code § 190.1.

- People v. McDaniel, 12 Cal.5th 284 (Cal. 2021).

- I am vehemently opposed to the death penalty, especially in light of the racial disparities of who it is applied to and the fact that numerous people have been found innocent after being sentenced to capital punishment.

- https://www.cdc.gov/museum/timeline/covid19.html.

- Ibid.

- The facts in this section come entirely from the complaint in a case wherein I represent the family of the decedent.

- https://www.prisonstudies.org/highest-to-lowest/prison-population-total?field_region_taxonomy_tid=All.

- 429 U.S. 97 (1976).

- https://whyy.org/articles/report-long-waits-for-health-care-outdated-technology-at-vaughn-prison/.

- https://healthandjusticejournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40352-021-00141-x.

- https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2017/10/prison-health-care-costs-and-quality.

- Ibid.

- https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical.

- https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-jails-privatization-special-report/special-report-u-s-jails-are-outsourcing-medical-care-and-the-death-toll-is-rising-idUSKBN27B1DH.

- Ibid.

- https://www.themarshallproject.org/2021/10/31/arizona-privatized-prison-health-care-to-save-money-but-at-what-cost.

- Supra, note 14.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- https://www.themarshallproject.org/2018/02/25/how-bad-is-prison-health-care-depends-on-who-s-watching?gclid=CjwKCAjwjtOTBhAvEiwASG4bCBBkLfaJ1MeW8YCpO0hmn8RxHl-kTbQ493HaPbQuGH-tabtmc7SfLhoCvD0QAvD_BwE.

- https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/usa-jails-privatization/.

- https://jech.bmj.com/content/63/11/912.

- https://www.prisonpolicy.org/research/mental_health/.

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/thomasbrewster/2020/04/08/all-american-prisoners-have-been-promised-coronavirus-surgical-masks—a-nonprofit-for-the-blind-won-a-13-million-contract-to-deliver-them/?sh=74624a963e2a.

- https://www.themarshallproject.org/2020/03/06/when-purell-is-contraband-how-do-you-contain-coronavirus.

- Ibid.

- https://www.reference.com/world-view/average-size-prison-cell-ab1f1105c4872dd5.

- https://covidprisonproject.com/.

- https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/impact-covid-19-state-and-federal-prisons-march-2020-february-2021.

- https://covidprisonproject.com/blog/.

- Ibid.

- https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/07/us/inmates-incarceratedcovid-deaths.html

- Ibid.

- https://usafacts.org/articles/how-many-people-in-prisons-died-of-covid-19/.

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronavirus/in-depth/coronavirus-long-term-effects/art-20490351.

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-022-01909-w#Sec7.

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2022/09/29/prison-release-covid-pandemic-incarceration/.

- Ibid.

This article was originally published by Verdict Magazine.