PARMELEE, S.D. — Weldon Poor Bear received a powerful gift on Father’s Day 35 years ago: the birth of identical twin sons.

PARMELEE, S.D. — Weldon Poor Bear received a powerful gift on Father’s Day 35 years ago: the birth of identical twin sons.

He fondly recalls raising them in the traditions of their native Lakota heritage, with sweat lodges, ceremonial pipes and sun dances. There were baseball games and cross-country meets — and his son Adam’s ambition to become a police officer.

But memories are all that remain of Poor Bear’s biological children.

Near midnight on March 14, 2018, Poor Bear stood outside his house on the Rosebud Indian Reservation and watched, then listened, as Adam was shot and killed by a tribal police officer.

Adam was unarmed, according to official records in the case.

It was a profoundly personal loss for Poor Bear, who had already lost Adam’s twin, Arthur, to suicide a decade before.

But Adam’s killing is also part of an alarming and rarely discussed trend that has made Native Americans more likely than any other racial group to die in encounters with law enforcement.

Despite witnessing some parts of Adam’s fatal encounter — including seeing him run from police and hearing the gunshot that ended his life — Poor Bear remains largely in the dark about why and how his son was killed that night.

While accurate counts and solid information are difficult to come by, one thing is clear: Poor Bear is far from alone in mourning a Native American loved one killed by police — and searching in vain for answers.

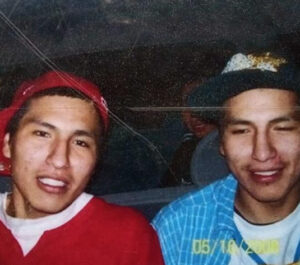

Adam Poor Bear (left) and his brother, Arthur, are shown in this 2008 photo. Adam — whose nickname was “Skinny” and whose Lakota name was Mato Ohitika — died after a Rosebud

Adam Poor Bear (left) and his brother, Arthur, are shown in this 2008 photo. Adam — whose nickname was “Skinny” and whose Lakota name was Mato Ohitika — died after a Rosebud Sioux tribal police officer shot him in 2018. Arthur died by suicide a decade earlier.[/caption]

A Lee Enterprises Public Service Journalism Team investigation examined deaths of Native Americans in encounters with law enforcement over the past 10 years, with a focus on the on- and off-reservation communities of South Dakota, where such fatal encounters are particularly common.

Interviews with dozens of surviving family members, law enforcement officers, attorneys and others — as well as reporting trips to Native American communities both on and off tribal land and the examination of lawsuits, police records and other documents and data — give new insight about the forces that have been fueling these deaths.

This investigation found:

-

Across the United States, Native Americans died at a significantly higher rate than any other racial or ethnic group in police encounters between 2017 and 2020.

-

A lack of funding for police in tribal communities contributed to fatal law enforcement incidents both on and off tribal lands.

-

Loved ones of those who died in police pursuits, police shootings and jails struggle to access even the most basic information about how these deaths occur.

-

A lack of accountability and oversight in the case of such deaths exacerbates distrust between Native Americans and law enforcement.

-

Such deaths often go unreported by media.

Salomon Zavala, a Los Angeles-based civil rights attorney who has worked with families of Native people killed by the police, said the length of the FBI’s response time can preclude families from pursuing excessive force and wrongful death cases, which typically have a two-year statute of limitations. And he said the difficulty in obtaining documents seriously complicates efforts to root out bad cops and pursue broader reforms that might bring down the high rates of fatal encounters between Natives and law enforcement.

Such accountability can’t be achieved, he said, without documentation.

“If you don’t have documents to evaluate and determine what exactly happened, then how do you hold someone accountable?” Zavala said. “How do you know these agencies, these police officers, these detectives are compliant with the law?”

This article was originally published by Rapid City Journal and writen by Ted McDermott, Public Service

Journalism Team