Overview

Overview

The right to assemble in protest is enshrined in the First Amendment of the United States Constitution, which states:

The Government shall make no law respecting the establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof, or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press or of the people to peaceably assemble and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

Throughout our nation’s history from the Abolitionist movement to the struggle for the Rights of Workers, Women’s Suffrage, Civil Rights and the Anti-War movements, this right has shaped and tested the bounds of American democracy.

In the nearly two and half decades since 9/11, the ongoing tension between the rights and freedoms of individuals and government authority has shifted the balance decidedly in favor of authoritarian state control.

Facilitated by the imposition of anti-democratic measures, such as the Patriot Acts I and II, which allowed the government to conduct mass surveillance of people in the U.S. and tightened control over financial institutions offering bank accounts, the ever-increasing militarization and federalization of police, and a monopolist, fear-mongering media peddling disinformation, American democracy hangs by a tenuous thread.

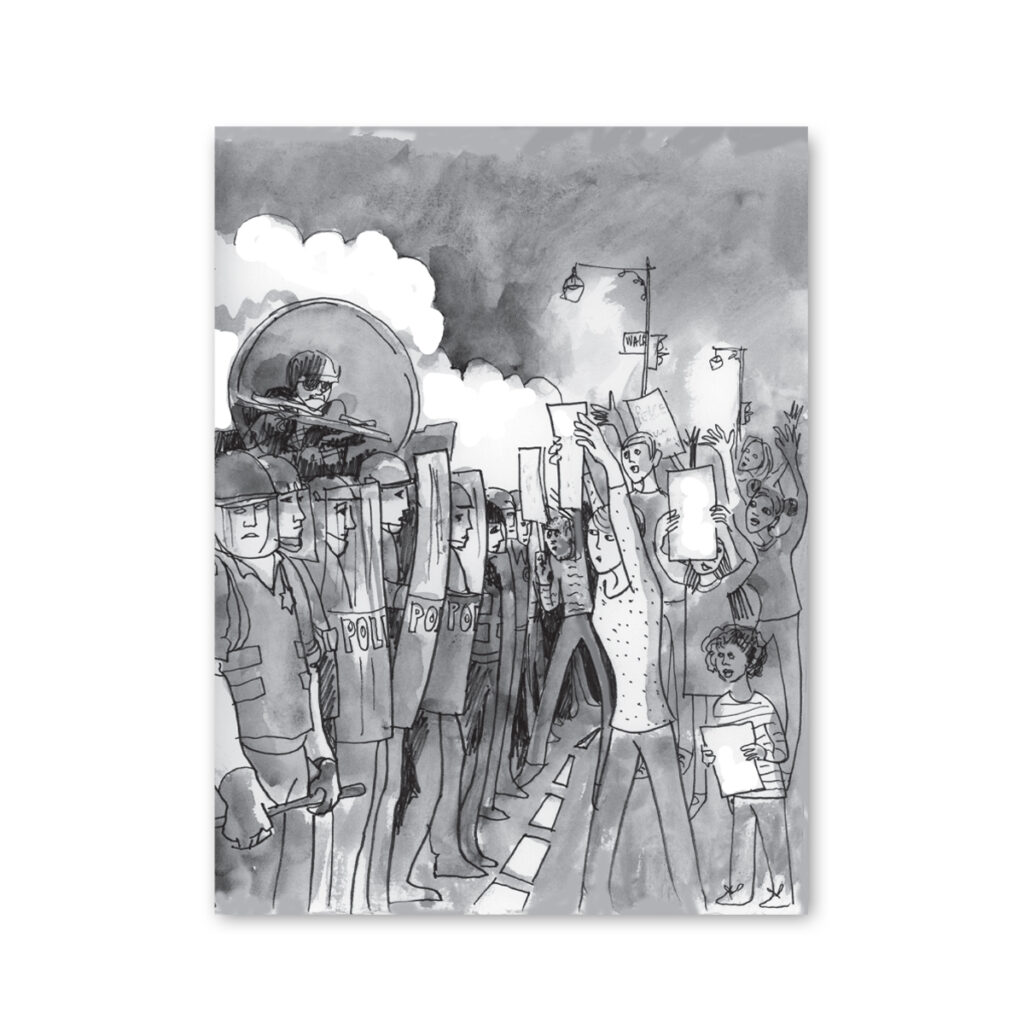

Most recently, collective action in protest of rampant police violence, the subversion of environmental protections and the sovereignty of indigenous peoples has returned the question of public dissent and repressive state responses to the national spotlight.

In this article, I examine how militarized police forces in the U.S. violently repress protesters exercising their First Amendment rights. I discuss police abuse against people, mostly of color, calling for the end of police brutality and people, mostly indigenous, seeking to curtail the destruction of indigenous lands by the Dakota Pipeline at Standing Rock. Lastly, I offer direction for attainable measures for reform to be implemented and effected.

But first, my own experience, at an early age, of government repression of social dissent.

Los Angeles Uprising, 1992

Los Angeles Uprising, 1992

My introduction to social protests and government repression came during the 1992 Los Angeles Uprising.

This event marked a major change in global consciousness regarding the true gravity of police violence and misconduct in the U.S. and awakened many to the complicity of the judiciary in the unlawfulness.

On March 3, 1991, Los Angeles police pursued Rodney King in a high-speed car chase; four officers then savagely beat him with batons, while a dozen other cops stood by and watched, and bystanders yelled, “Don’t kill him.” King suffered a skull fracture, broken bones and permanent brain damage. A man watching from his window happened to capture the assault on video, which he sent to a local TV station, and soon the video appeared on newscasts across the country. The famous footage of police viciously beating a black man offering no resistance put the aggression, brutality and humiliation that we residents of South Central Los Angeles and other low-income communities of color suffered daily, on display for all to see.

So commonplace was this mistreatment that it was not until the eyes of the nation turned to the trial of the four police officers caught on camera assaulting Rodney King in anticipation of a potential guilty verdict, that many of us even conceived the possibility that police might be held accountable for wrongdoing.

When the local jury acquitted the four cops, the faint glimmer of hope was extinguished. Everyone who had seen themselves in Rodney King — Black and Mexican, men and women, young and old — understood the message of the verdict that could not have been more resounding: “You don’t count. Your lives don’t matter.”

While neither premeditated nor organized, the ensuing explosion of fury was a legitimate expression of the collective pain and accumulated frustration that we all felt. It was a surreal experience watching my neighborhood burning on live television, then stepping out of my front door and seeing and smelling the fires.

For two weeks, my neighborhood was at the center of global media. Much was made of the looting and destruction of private property and President George H. W. Bush‘s declaration of a State of Emergency and deployment of the National Guard followed by his sending in 3,500 federal troops. This was the first significant federal military occupation of Los Angeles since the 1894 Pullman Strike and the first federal military intervention in an American city to quell a civil disorder since the 1968 assassination of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

I watched armored personnel carriers and tanks roll past my house driven by National Guard members dressed in army fatigues. It was the first time I realized how quickly a domestic environment could be transformed into a military theater through federalized police intervention, creating an “us vs. them” dynamic wherein residents were deemed enemy combatants.

That one unjust verdict could unleash such convulsive upheaval crystallized in my mind the existential power of the law to bring balance or chaos to society, and spurred me to become an attorney.

Our uprising echoed the often forgotten and overlooked Zoot Suit Uprising of 1943, which was triggered by similar incidents of police and military violence targeting Mexican Americans in Los Angeles, as well as those in locations targeting African Americans like Watts, Detroit, Washington, D.C., Baltimore and Kansas City following the assassination of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1968.

Protests Against Police Brutality and Racial Inequality

Protests Against Police Brutality and Racial Inequality

The latest wave of collective action directly addressing police brutality and racial inequality in America began in 2013 with the acquittal of George Zimmerman, a private security guard caught on an audio recording killing unarmed 17-year-old Trayvon Martin in Florida. Zimmerman claimed the murder was self-defense, as he lived in a gated community where there had been incidences of break-ins and stolen property. Upon seeing Martin, who was a young, black man, walking through the neighborhood returning to the house where Martin was staying, Zimmerman, after reporting to police that Martin was suspicious, proceeded to shoot him.

Outrage quickly spread, as the acquittal was a reminder of how often those who use deadly force against Black and Brown people, whether law enforcement or private citizens, face no legal repercussions for their abuses.

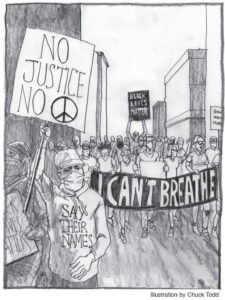

Successive protest actions spawned the Black Lives Matter movement, which became international after the police killings of two more Black men, Michael Brown near St. Louis and Eric Garner in New York City.

Civil dissent reached a boiling point following the video-recorded killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, which also followed the police murders of Breonna Taylor in Louisville, and 12-year-old Tamir Rice in Cleveland, among many others. In 2020, while protesters flooded the streets of cities around the world, many of those in the U.S. calling for an end to police brutality, were met with military-style police violence — a tragic irony.

Watching it unfold, my mind returned to South Central in 1992, as I recognized the parallels and the unfortunate fact that little had improved, especially for marginalized Black, Brown and Indigenous peoples.

Dakota Access Pipeline at Standing Rock

Dakota Access Pipeline at Standing Rock

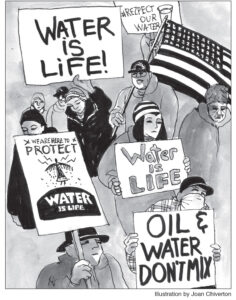

The youth-initiated opposition to the Dakota Access Pipeline near the Standing Rock Reservation in North Dakota during 2016 and 2017 reflects the inseparable coupling of environmental protection and indigenous sovereignty.

Sparked by highly valid concerns regarding the pipeline’s endangerment of groundwater, the protests garnered national and international support and were met with heavily militarized law enforcement and its brutal campaign of violent repression.

From my perspective, the demonstrations took place within a constitutional double bind. Either the Standing Rock Sioux are a sovereign people defending their land and water rights as guaranteed by the 1851 Treaty of Traverse des Sioux and the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, both of which were ratified by the U.S. Senate and affirm the Sioux as a sovereign nation, and/or the demonstrators at Standing Rock are U.S. citizens exercising their constitutionally protected First Amendment Right to peaceably assemble and petition the Government for redress of grievances.

Regardless, both views make clear that Indigenous People and their allies stood squarely within their rights, while the constellation of energy companies, private security firms, law enforcement and local prosecutors arrayed against them were in violation of the U.S. Constitution.

The pipeline and the government’s militaristic intervention contravened the United States’ 2010 endorsement of the United Nations Declaration on The Rights of Indigenous People, which proclaims, “a historic body of collective rights of Indigenous Peoples and individuals,” including, for the first time in history, “the right to exist.”

Central to the Declaration is the Free and Prior Informed Consent clause which “allows Indigenous Peoples to provide, withhold, or withdraw consent at any point, regarding projects impacting their territories.” Yet on January 24, 2017, only four days into his term, President Trump ended the review process with an executive memorandum, allowing the project to go forward without any input from affected tribal stakeholders, opening the door to crushing repression by law enforcement.

The tactics and weaponry employed against Standing Rock protesters included publicly strip-searching female demonstrators, leaving them freezing and naked in cells for hours, the release of unlicensed attack dogs, and use of water cannons in freezing temperatures and so-called less-lethal weapons, such as pepper-spray, mace, bean-bag shotgun projectiles, concussion grenades, long-range acoustic devices and armored personnel carriers — all of which is excessive and abhorrent; much of which is unlawful.

Police Repression and Less-Lethal Weapons

Police Repression and Less-Lethal Weapons

At protest actions that have taken place against police brutality, authorities have employed an ever-growing arsenal of “less-lethal” weapons as well as those used at Standing Rock. Policing forces have used tear gas, rubber bullets, electro-shock rubber bullets, and rubber buckshots, polymer, plastic, and wax bullets, sponge grenades, ring airfoil projectiles and a class of long-range acoustic devices that make use of sound to incapacitate a human target.

According to Scientific American, such weapons “can still cause serious injury,” including blindness, paralysis and a host of other complications resulting in acute and long-term trauma.

My client, Marisa Baltazar, a young woman who attended a Black Lives Matter protest in Long Beach, California on May 31, 2020, suffered a partially amputated finger after being struck by a “less-lethal” projectile fired by a member of the Long Beach Police Department.

Ms. Baltazar had been filming the police with her phone, which she was holding close to her face, when without warning or provocation, she was struck by a police projectile. Had it not been for her phone which deflected part of the projectile, she would have been struck in the eye causing further permanent damage.

A 2009 Wayne State study found that such projectiles can strike with a force twice that of being punched by a professional boxer; strong “enough to fracture cada‑ver skulls.”

A 2017 UK study of 1,984 people shot with “kinetic impact projectiles” showed that 3% died because of their use and 15% sustained some form of permanent injury.

Ostensibly these weapons give law enforcement options other than firearms in circumstances where lethal force is unwarranted. Yet, as in my client’s case, they are broadly deployed against peaceful protesters, causing grievous bodily and psychological harm.

“My life will never be the same,” Ms. Baltazar confirmed at a press conference we held to announce the filing of her lawsuit against the police department. “I am not able to do basic things, help myself, cook, shower, help my daughter; mentally I am not okay.”

Her plight reveals the central tension playing out at the center of our democracy — individuals exercising their inalienable First Amendment rights are being violently assaulted, brutally intimidated and treated as criminals.

Human Rights Violations and the Criminalization of Dissent

Disappointingly, our legal system has been complicit with law enforcement in the steady and incremental erosion of our First Amendment rights. A host of legal mechanisms have been manufactured to effectively criminalize dissent. Baseless charges of disorderly conduct, obstruction of justice, unlawful assembly, resisting arrest and the designation of groups as “terrorist organizations,” have all been applied to arrest and remove demonstrators.

Internal documents circulated by TigerSwan, a private security contractor at Standing Rock, attempted to characterize indigenous opposition as an “ideologically driven insurgency with a strong religious component,” one that operated on a “jihadist insurgency model.” Aside from being patently absurd and untrue, the document offers a telling insight into the strategic objective of reactionary forces, equating dissent with terrorism to thereby justify full-scale military action.

With this in mind, another equally disturbing precedent also bears citing. During the 1999 protests against the World Trade Organization (WTO) in Seattle, the entire downtown core was unilaterally declared a “no-protest zone,” an invented designation that empowered police to arbitrarily arrest anyone who “appeared” to be expressing opposition to the WTO. This included wearing pins, holding signs and verbal expressions. Though such police tactics rarely hold up to legal scrutiny in the long-term, they satisfy the short-term objective of removing protesters and squelching public expressions of dissent.

Recommendations

The following are some concrete recommendations to facilitate the restoration of First Amendment rights.

1. Mandatory Use of Body Cameras: Currently only seven states mandate use of body cameras by police. A bright spot in reform efforts, according to the National Institute of Justice, body cameras have shown promise in reducing citizen fatalities in jurisdictions such as Las Vegas, Phoenix and Rialto, California.

Nonetheless, body cameras are far from a panacea. According to an ACLU Washington report published June 7, 2021:

A comprehensive review of 70 empirical studies of body-worn cameras found that body cameras have not had statistically significant or consistent effects in decreasing police use of force. While some studies suggest that body cameras may offer benefits, others show either no impact or even possible negative effects. In 2017, researchers conducted one of the largest randomized control trials on body cameras that included over 2,000 police officers in Washington, DC, and found that body cameras had no statistically significant impact on officer use of force, civilian complaints, or arrests for disorderly conduct by officers. In other words, body cameras did not reduce police misconduct. A 2020 meta-analysis similarly found substantial uncertainty about whether body cameras can reduce officer use of force. A recent 2021 study did find that on average, body cameras reduced use of force by nearly 10%, but the study’s authors noted that their results may have been inflated by site-selection bias. The authors also acknowledged that body cameras are not a panacea to police violence. While in a few high-profile cases, body camera footage has been used in trials that led to officer convictions, body camera footage is disproportionately used to prosecute civilians rather than officers. One 2016 study found that 92.6 percent of prosecutors’ offices in jurisdictions with body cameras have used that footage as evidence to prosecute civilians, while just 8.3 percent have used it to prosecute police officers.

2. Demilitarization of Police: The Department of Defense has transferred over 7 billion dollars’ worth of military-grade hardware to police since 1990. This transfer ramped up exponentially post 9/11 with the passage of Patriot Acts I and II. The result, according to nonprofit National Priorities, is that “law enforcement has treated American Cities like war zones, and bystanders and protesters as enemy combatants.”

According to the American Bar Association Journal, local SWAT teams in American cities violently break into private homes more than 100 times per day. The vast majority of these raids are to enforce laws against consensual crimes (such as drug sales). In many cities, police departments have given up the traditional blue uniforms for “battle dress uniforms” modeled after soldier attire.

Police departments across the country now have assault rifles, concussion grenades and some have helicopters, tanks, Humvees and armored personnel carriers (Mine Resistant Ambush Protected vehicles, or MRAPs) designed for use on a battlefield that became ubiquitous in the U.S. military presence in Iraq and Afghanistan. The federal government turned these weapons over to local police forces. Many SWAT teams today are trained by current and former personnel from special forces units like the Navy SEALs or Army Rangers. National Guard helicopters now routinely swoop through rural areas in search of pot plants and, when they find something, send gun-toting troops dressed for battle rappelling down to chop and confiscate the contraband.

The 1033 Program, named for a section of the National Defense Authorization Act, has provided congressional approval for upwards of $4.3 billion in military equipment to flow to police forces throughout the country. The program quickly gained popularity among police chiefs for the high firepower and low costs. Some police forces in communities such as Watertown, Connecticut, have purchased MRAPs, originally priced over $700,000 each, for as little as $2,800.

These draconian acts were imposed on the country under extreme duress and under provably false pretenses. In theory and application, they serve to nullify the Bill of Rights and abridge the personal freedoms of all.

3. Retrain and Educate Officers: It is not enough that police be trained in nonviolent crowd control, de-escalation and protest management techniques. It is also imperative that they be familiar with the language and ethos of the U.S. Constitution and have a solid understanding of the rights protected therein.

4. Officer Accountability: Officer misconduct has long been enabled by written and unwritten norms protecting law enforcement from personal liability for their misdeeds. The U.S. Supreme Court created the notion of “qualified immunity” to limit civil liability of government officials, including police officers. The court has then made it increasingly difficult for any plaintiff to get past the immunity bar. This must change. Officers should be both criminally and civilly liable for crimes committed on-duty. The badge should not be a legal shield offering carte blanche immunity.

5. Re-imagine Policing: Efforts are underway in cities across America to rethink the role of police in emergency and non-emergency response. These efforts should be encouraged and expanded. The question must be asked, “Is it appropriate for police to patrol protests against police brutality?”

Final Words

“Rather than seeing peaceful protest as a democratic means of participation, too often governments resort to repression to suppress protests and silence people’s voices,” said Clément N. Voule, UN Special Rapporteur on the right to peaceful assembly and of association in a report presented to the United Nations Human Rights Council in 2022. Voule noted in his report that governments around the world were utilizing military-style tactics to quash peaceful protests, which has led to an escalation of human rights abuses.

Although the federal government in the United States may claim that protests are the purview of local police departments at the direction of sovereign States, it is abundantly clear that the federal government could do a lot more to hold those State actors accountable, including receiverships and consent decrees and prosecuting officers who abuse their authority. Although perhaps not legally responsible, the federal government is complicit in these abuses and erosion of First Amendment rights, and, as such, is morally responsible.

Editor’s Afterword: Government efforts to suppress protests escalated with the September 5, 2023 unprecedented indictment of 61 “Cop City” protesters under Georgia’s state Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Law (RICO). “Cop City” refers to the Atlanta Public Safety Training Center, an 85-acre, $90 million facility being built for massive militarized police training, where the police plan to simulate real-world situations, including a mock urban space to practice urban warfare.

Five protesters were also charged with domestic terrorism and three with money laundering and charities fraud. This followed the fatal police shooting in January 2023 of Cop City protester Manuel Paez Teran; what led to police firing 57 bullets into Mr. Teran remains unclear.

For two years, protesters have strenuously opposed the center’s construction both for militarizing the police and for environmental reasons. Cop City will be located in the middle of South River Forest, Atlanta’s largest green space. Construction required clearcutting a large swath of the forest canopy, lowering air quality because the forests absorb 19 million pounds of pollutants every year. It will likely cause a 10-degree temperature rise in surrounding areas which house mostly low-income Black residents.

The indictment describes at length the supposed beliefs of the alleged co-conspirators and recites 225 overt acts, which include distributing leaflets and providing money for bail and legal defense. Attorney Lauren Regan, Executive Director of the Civil Liberties Defense Center, which represents activists who are criminally charged, called the indictment an “attempt to criminalize the movement itself, not the individual,” which she said is “clearly intended to chill larger political participation.”

The indictments are reminiscent of the State of Alabama’s actions during the civil rights movement banning the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) from activities statewide and then subpoenaing the NAACP’s membership lists. This was after bringing in 80 indictments for conspiracy against leaders of the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott. While the Supreme Court thereafter upheld freedom of association and the right of individuals to band together and act, RICO represents a potential prior restraint on protest activities, based on the threat of severe penalties and provisions regarding conspiracy to commit a RICO offense.

Salomon Zavala is the founder and managing attorney at Zavala Law Group and Executive Director of Ollin Law.

A first-generation Chicano, Mr. Zavala was raised by his single Mexican immigrant mother in the Florence District of South Central Los Angeles during the 1980s and 90s. He witnessed first-hand the consequences of mass incarceration and tough-on-crime policies. Those early memories fuel his passion for his legal work and commitment to justice.

Mr. Zavala graduated from the University of California, Berkeley, School of Law after earning a Bachelor of Arts degree in Sociology from Amherst College. His awareness of the injustices of the American legal system inspired him to co-found Ollin Law in 2013. Ollin Law infuses indigenous justice principles into the adversarial and punitive structure of the U.S. justice system. Mr. Zavala’s work in and out of court focuses on prison reform/abolition, alternatives to incarceration and indigenous peoples’ rights. Mr. Zavala’s civil rights practice helps clients with a range of matters, including wrongful convictions, police brutality cases, prison litigation and resentencing hearings. He also helps deportees with criminal justice and immigration issues. He has conducted legal clinics and trainings on these and other topics throughout the U.S. and Mexico.

In addition to his work at Ollin Law, Mr. Zavala serves on the boards of various community-based nonprofits, including Tzicatl Community Development Corporation, an indigenous community development organization, and The Community Based Public Safety Collective, a victims/survivors advocacy and community safety organization. Mr. Zavala is a member of CCLP.

This article was originally published by Verdict.